1839 prison could be breakout attraction, economic draw

Driving by the original Iowa State Penitentiary in Fort Madison, I always wondered if the offenders housed within were tormented by happy sounds emanating from the miniature golf and ice cream stand located just outside its sandstone walls. This past weekend, I found out.

Nothing from the outside penetrates the razor wire and thick rocks that jut several feet skyward, surrounding the buildings and yard. A blessing? A curse? I honestly can’t say.

The facility, established nearly a decade before Iowa became a state, has been effectively shuttered since Aug. 1, 2015, when more than 500 offenders were bused to the state’s new Iowa State Penitentiary, built a little more than a mile away on a site that once housed a prison farm.

Historic Iowa State Penitentiary Inc., a nonprofit determined to either preserve or repurpose the old prison, puts the time line in perspective: “Our nation was only 57 years old when it was constructed, with only 26 states in the union. Iowa was a territory, with (the facility) acting as the territorial prison almost a decade prior to Iowa’s statehood. It was 22 years old at the beginning of the Civil War, and had seen its 100th birthday before the end of World War II.”

It was this nonprofit, in collaboration with the Iowa Department of Corrections, that organized tours. For just the second time since the prison closed, the public was able to take a peek inside.

The first tours, held in May, drew a crowd of more than 3,500 people. Hundreds more, many of whom waited in line for hours, had to be turned away at the end of the day. The cost of admission for those first tours was an item for local food pantries, and more than 14,000 pounds was collected.

Admission to the 10-acre site on the banks of the Mississippi River last weekend was $15 for those ages 12 and up. More than 2,200 people braved intermittent rain showers to stand in line and walk the grounds, none grumbling about the price tag.

The facility represents 176 years of territory and state history; it is the oldest continually used prison west of the Mississippi. Its first prisoners also were its construction crew, many sleeping in makeshift foxholes until the shelter was complete. Forty-six men swung from gallows on the site; tens of thousands of Iowans traveled to watch the macabre events. With far less fanfare, many more offenders died of old age or disease behind the prison’s sandstone walls. Hundreds of Iowans earned a paycheck while working there, and hundreds more were called to volunteer.

And, in order for even a portion of it to be preserved, the site must undergo a federally mandated Historic Structures Report to “formally evaluate the site’s property condition” and “provide recommendations as to the adaptive reuse.” Without such an assessment, which is expected to cost between $150,000 and $200,000, the Iowa Department of Corrections can’t release the property to a nonprofit or the public sector for further development.

Based on last weekend’s tour attendance, the nonprofit raised about $33,000. The group also is selling merchandise — mugs, T-shirts, magnets, etc. — and plans to use those proceeds to fund the property assessment.

But the rest of the money needs to come sooner rather than later. Buildings on the site, some damaged in a 2015 storm, are deteriorating. Tours last weekend omitted many historic locations on the site, including the on-site theater where movies were shown and prisoners performed in an annual talent show.

“Are we not touring that part of the building because of time constraints or because of decay?” I asked our guide, a former corrections officer at the facility. She frowned before flatly responding, “Decay.”

Later, as we exited the “chow hall,” located on the ground floor of the building with the theater, I spotted a tree or bush growing from its rooftop. Shattered and missing windows mar the facade.

It’s this level of deterioration that led Preservation Iowa to place the prison on its 2017 “most endangered properties” list.

Since there are no immediate plans to open the prison to the public again, those wanting to learn more will need to seek other opportunities. Dan Manatt, a Democracy Films director, has released a documentary, “The Fort: Three Centuries of Crime and Punishment in the Iowa State Penitentiary.” It weaves interviews with prison staff and offenders with a history of the facility. Jack Nutter, the fifth-longest-serving inmate in the nation who entered the Iowa prison in 1956 when he was 18, is one of the people featured.

The film shows how corrections has changed and, more important, how the Fort Madison facility’s original and subsequent construction and updates are essentially a time capsule. Three main cellhouses built between 1906 and 1920 offered significant improvements from the original structure, just as state-of-the-art construction at the new facility dwarfed them. Technology advanced, structures were redesigned and populations have changed, too. As Manatt notes in the film, only 4 percent of the prison population in 1839 were serving life sentences; now 70 percent face “all day and a night.”

Residents in and around Fort Madison once spent Sunday afternoons inside the prison, watching baseball games. But the games ended as violence escalated in the facility. The culmination of those tensions came in 1981 when inmates took 12 hostages and gained control of the facility. All the hostages eventually were released unharmed, but a Lee County sheriff’s deputy was injured. One offender was stabbed and another, Gary Eugene Tyson, had been murdered in what court cases later detailed as gang-related violence.

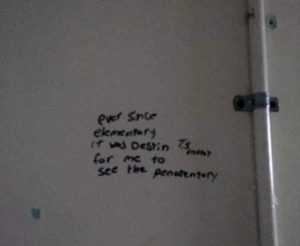

A tour of the now-closed facility reveals gang activity was a continued presence. Cell walls and surfaces serve as canvases for gang logos, signatures, art and messages. Paint layers and fading signal what’s most recent.

The old Iowa State Pen is a lot like its own history — massive and surprising. Standing in the middle of it changes your perspective.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on Oct. 15. 2017.