Key pathways in Iowa’s quest to reduce recidivism are initiatives the Department of Corrections can’t initiate.

About 95 percent of the Iowa prison population will eventually be returned to local communities. For several years, the Iowa Department of Corrections has explored ways to reduce the number of those who return to state custody.

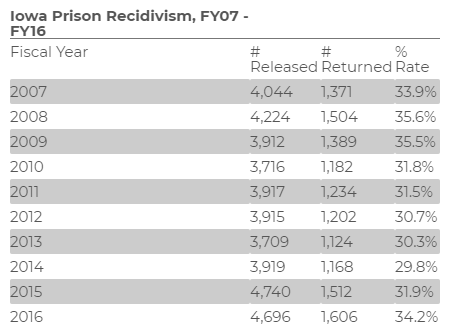

And, until recently, departmental efforts have been paying off. In 2014, recidivism fell to 29.7 percent — down from a staggering 45 percent 15 years earlier. But recidivism is once again climbing. It was 34.2 percent for 2016, the most recent figures available.

This year marks the end of a $3 million, three-year Second Chance Grant from the U.S. Department of Justice aimed at reducing recidivism and, ultimately, overall prison population.

The recidivism rate is the percent of people released from prison or work release who returned to state custody within three years. Releases tracked by the Department of Corrections are paroles, discharges due to end of sentence, and sex offender releases to special sentence supervision. The reporting year is the conclusion of the three-year tracking period for a release group. For instance, the fiscal year 2016 rates describe recidivism for people leaving state custody during fiscal year 2013.

Because of how the rate is calculated, Iowans have not yet seen the full impact of evidence-based initiatives undertaken as part of partnerships through the Second Chance Grant. But we do know from other national research that two key ways of keeping people from returning to prison aren’t changes the DOC can make on its own. Both require legislative action.

Research from the University of California-Berkeley found people with felony convictions who had voting rights permanently stripped were significantly more likely to commit another crime. Studies by the Florida Parole Commission and other groups repeat these findings.

Yet Iowa remains as one of only four states that chooses to permanently disenfranchise felons. A bipartisan bill before the Legislature aims change the law, at least for non-violent offenders, but does not appear to have widespread support.

A different study released this month shows connections between wages and recidivism. Research by economists Michael Makowsky of Clemson University and Amanda Agan of Rutgers University found that for every dollar increase in the minimum wage, one percentage point could be shaved off recidivism.

Iowa workers haven’t seen a minimum-wage increase in a decade, although workers in 18 other states, including five neighboring states, have had wage improvements. A handful of Iowa counties — including Johnson and Linn — previously passed minimum wage increases, only to have their efforts pre-empted by the 2017 Iowa Legislature.

Iowa, also unlike its neighbors and the nation, experienced prison population increases during three of the past four years. In 2017, Iowa prisons were at 115 percent capacity.

The last statistic alone should be enough to prompt lawmakers to put all the tools in their policy toolbox to use.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on February 24, 2018. Photo credit: Stephen Mally/The Gazette