The new National Health Security Preparedness Index is out, and Iowans continue to lag behind in plans for the state’s most vulnerable.

Across most of the 139 measures used to compile the index, Iowans fare well with rankings at or slightly above the national average.

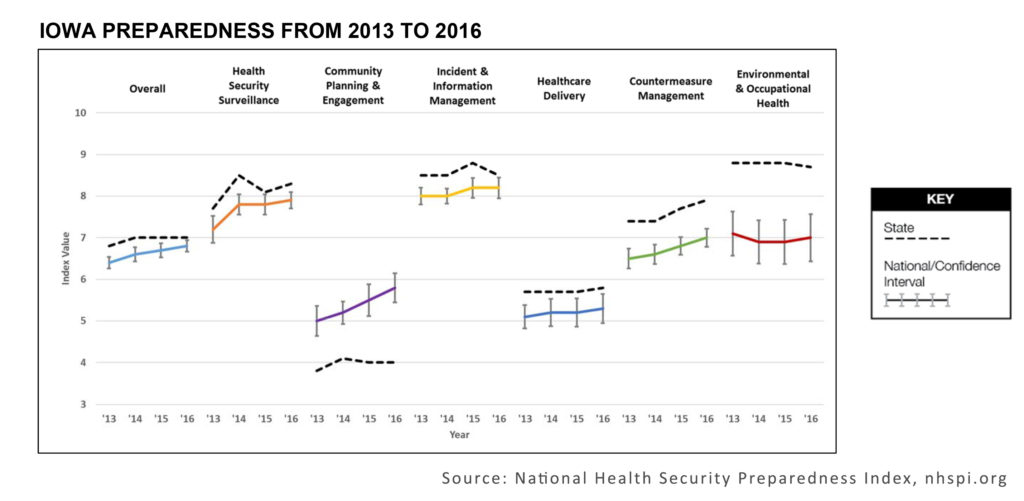

Iowa gets an overall score of 7 out of 10 — the same score it’s had for the past three years. But while Iowa has stagnated, other states have improved. The 7 that placed Iowa above the pack in 2014, now puts it in the middle.

Drilling further down, it’s apparent that there is one section in particular where Iowans are lagging behind. Index authors labeled it as “Community Planning and Engagement Coordination,” which includes actions taken to develop and maintain supportive relationships among government agencies, community organizations and individual households. Essentially, it is our ability and commitment to work and plan together for disasters and emergencies.

The national average for this subsection is 5.8, which means Iowans aren’t alone in their struggles. But with a score of 4 out of 10, Iowa ranks dead last. It’s even outpaced by Alaska, the state with the lowest overall index score, which received a 5.2 for Community Planning and Engagement. The average score for bordering states is 5.8, with Nebraska’s 7.2 leading the way.

And it should be noted that this year isn’t an outlier for the Hawkeye State. Iowa has received nearly the same score for the past four years.

Being from Eastern Iowa where I’ve watched people come together to fight and clean up after natural disasters, I found this particular measure a hard pill to swallow. Why is a state I know to be so very capable, generous and resilient ranked so poorly?

Well, it isn’t because Iowans aren’t volunteering or aren’t participating in their communities. In that underlying measure, which focuses on neighbors helping neighbors, voter turnout and volunteer hours clocked each year, Iowa gets a 6 out of 10. Not too shabby.

The state receives a 4.6 score based on collaborations between hospitals, county health departments, emergency management and other entities. When considering the ability of those and other community entities to train, access and organize emergency volunteers, the state score is 3.1 on the index.

Bringing up the rear, is the state’s index score of 1.3 for its ability to protect those recognized as at-risk in the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act — the elderly, pregnant women and children — and those who require additional crisis assistance like the disabled, those lacking transportation, people from different cultures, or those living in institutions.

Plans — like how child care providers reunite families in times of crisis, or how schools respond to hazards — aren’t part of state reports. This forced researchers to look outside traditional information streams and score on a patchwork of indicators.

I could be an optimist and assume plans to protect the most vulnerable among us exist somewhere, or that most entities are voluntarily doing more than what the state requires. But when it comes to my children, I think I’d rather have it in writing.

[scribd id=346573170 key=key-VQhoLBZpC6GJRK70Iom8 mode=scroll]

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on April 29, 2017. Photo credit: National Health Security Preparedness Index