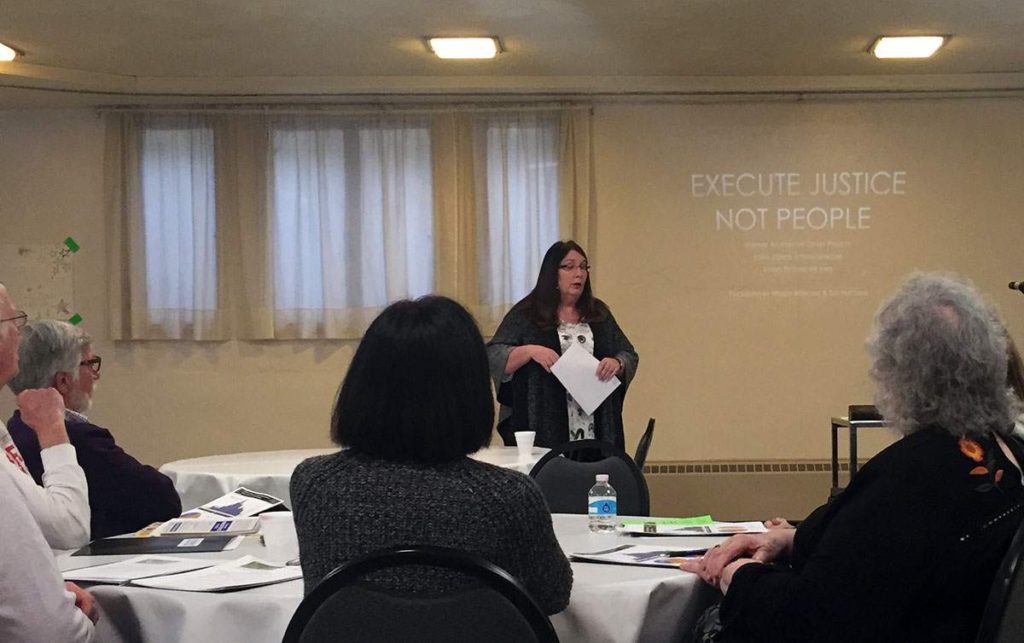

As state lawmakers consider reinstatement of the death penalty in Iowa, a coalition of opposition groups plans to travel the state as part of an information campaign. They began Monday night in Cedar Rapids.

“At the very least, we want Iowans to better understand what reinstating the death penalty will mean; how it will impact us all in a variety of ways,” said Sue Hutchins, a counselor who formerly worked in the Federal Bureau of Prisons and now helps lead Living Beyond the Bars, a support group for family and friends of inmates.

The local group is working with the bipartisan Iowans Against the Death Penalty and Iowa Justice Action Network to convene a series of information sessions.

“Iowans can have civil discourse on this issue,” said Wendy Wittrock, who spoke on behalf of Iowans Against the Death Penalty. “We can learn about the death penalty in Iowa, and we can evaluate its use elsewhere to decide if it’s something that needs to be replicated here.”

The last execution in Iowa took place March 5, 1963, in Fort Madison. A man convicted in federal court of killing a Dubuque doctor was hanged while the Iowa Senate debated a House-approved bill to abolish the death penalty. It was the last federal execution until 2001 and, two years later, Gov. Harold Hughes signed the bill that abolished Iowa’s death penalty.

Since that bill was signed, there have been periodic movements to bring back the death penalty, nearly all connected to rare but undeniably heinous crimes. The latest movement, Senate File 335, shares its origin with other recent proposals, which followed the abduction and killing of two Evansdale girls. While not yet part of the most recent bill, the shooting deaths of two Des Moines-area police officers in 2016 have prompted additional death penalty discussions.

Proponents of the measures say the death penalty would serve as a deterrent; that current Iowa law, which stops at life without parole, makes no distinction between those who kidnap and rape and those who kidnap, rape and murder, providing an incentive to silence witnesses.

But as Hutchins and Wittrock told those gathered in Cedar Rapids, data doesn’t back up this premise. That is, states with the death penalty consistently have higher murder rates than those without.

And while some may believe the death penalty results in reduced taxpayer burden, the opposite is true. Constitutional and procedural hurdles rightfully increase the cost of capital punishment cases into the millions — far more than the cost of life behind bars.

There also is the problem of wrongful convictions. As of last year, 161 people on death row had been exonerated.

Closer to home, two men who spent 25 years in Iowa prison for the 1977 murder of a Council Bluffs police officer were released in 2003. The Iowa Supreme Court ruled evidence proving their innocence was withheld by prosecutors.

If Iowa had the death penalty when these men were convicted, it’s unlikely they would have been alive to argue their innocence.

Considering these and other ramifications takes nothing away from grieving family members. It’s time to talk.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on Jan. 17, 2018.