Long-anticipated growth has finally come to rural Iowa, but is hardly the harbinger of prosperity so many wanted.

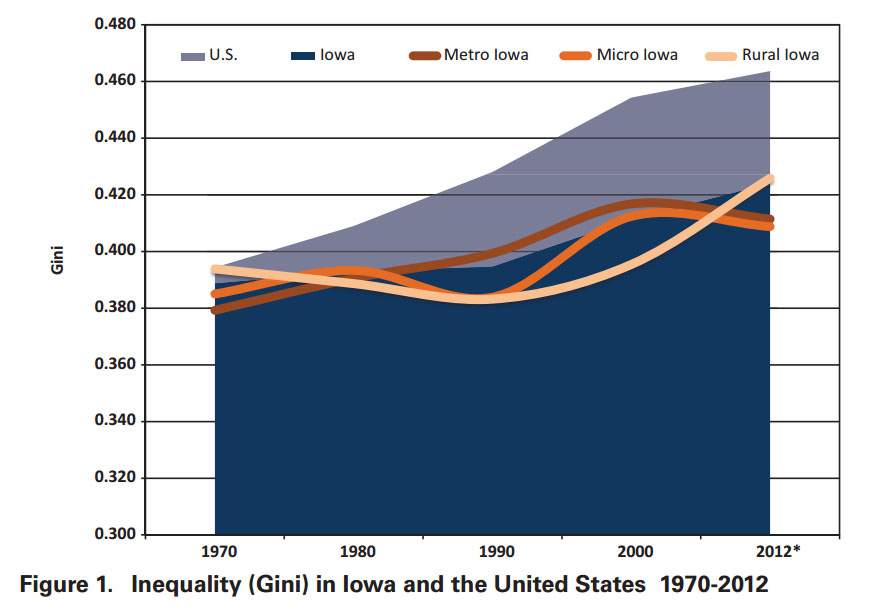

A study released this month by Iowa State University sociologist Dr. David Peters crunches 40 years of U.S. Census data, showing that income inequality in Iowa, like the rest of the country, is on the rise. And, for Iowans, such growth is now outpacing the nation, especially within our more rural counties.

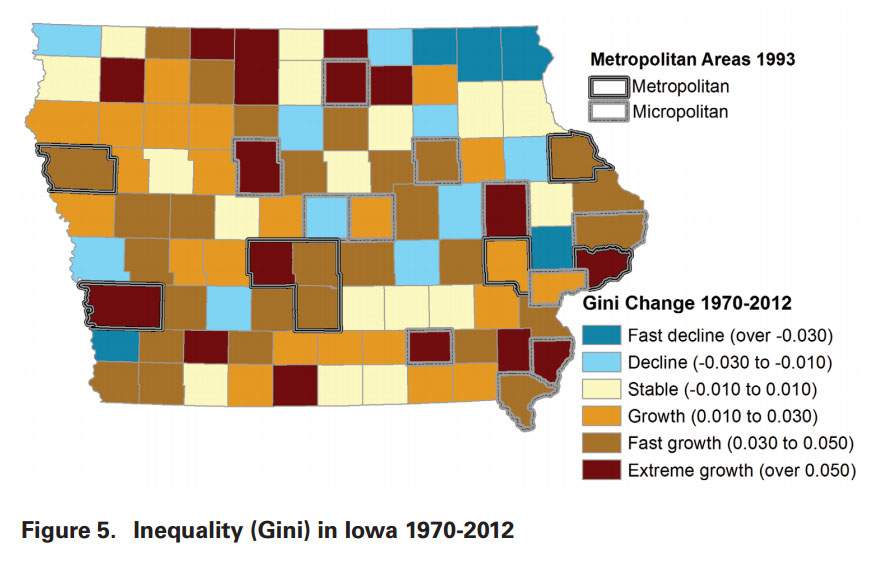

Deficiencies in some of these rural spaces are so stark as to rank among the 10 fastest growing places in the nation. They rank in the top 1 percent of American places for disparity growth — a situation Peters described as a “phenomenal jump” and “shocking” in The Des Moines Register.

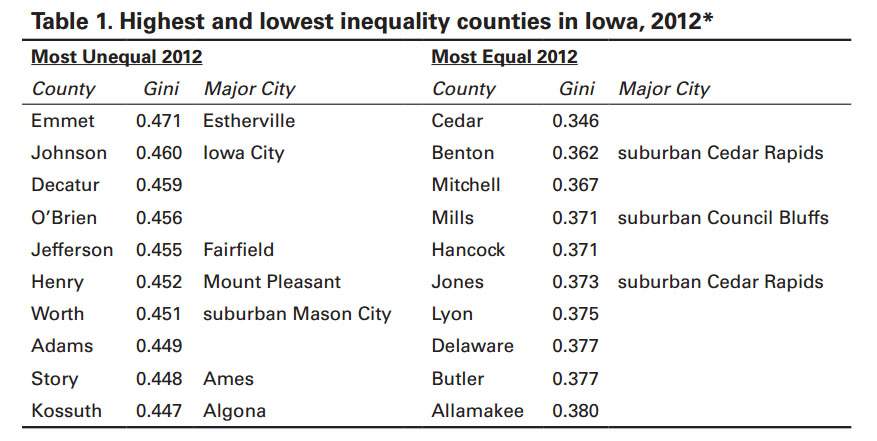

Counties ranking in the top 10 for wealth gap from 2000 to 2012 are Emmet (fifth), O’Brien (seventh) and Worth (ninth).

“Bottom earners have really taken a hit, especially since the last recession, and that’s what is driving inequality,” Peters explains. “The wage replacement for people who are laid off from middle-skilled, middle-wage jobs is much lower. They’re not able to recoup those wages and that’s where you see falling incomes.”

Unfortunately, the silver lining for rural counties is also a double-edged sword.

Because Peters can attribute much of the current disparity to growth in farm incomes, due to higher commodity prices, inequality will likely begin to stabilize in rural counties on the back of lower income for all.

Fewer farms and a lack of middle-skill jobs leave few options.

Eight of the 10 Iowa counties with the largest wealth gaps were rural. The other two contain university towns, which are economically influenced by student populations.

NOT JUST RURAL

While Iowa’s rural counties are showing larger inequality growth, their lower populations prevent them from being the largest contributors to the state’s overall wealth gap. Counties contributing the most are metropolitan centers — Polk County, Linn County, Johnson County and Scott County.

While the Hawkeye State has historically seen a low growth in income equality when compared to the rest of the nation — i.e., Iowa’s growth rate is 11.7 percent since 1970 compared to a 20.5 percent national rate — during the 2000s the state has surpassed national trends.

The end result is that Iowa, and the Midwest as a whole, has more equal incomes than most of the nation, but is polarizing faster.

Based on Peters’ research, the most unequal places in Iowa are rural, older and have a population that is more ethnically diverse. They also have more single-parent households, and tend to have a majority of either low-skill jobs in leisure and retail.

BUILDING COMMUNITY

It has been well-researched that wealth gaps negatively impact communities and can manifest as physical or mental health ailments, diminished academic success, higher crime rates, increased illicit drug use and addiction and diminished mobility. Contingent to these negative impacts is an inability to broadly function as communities.

When a county is stacked with lower income people, average wages often do not make ends meet. This results in many wage earners supplementing paychecks with already strapped social services. Limited wealth results in few contributing to the betterment of the programs or the communities.

Just as an individual living in poverty is subjected to a cognitive tax, limiting his or her ability make important decisions, communities can falter when their leaders and advocates are continually focused on how to provide for their own.

Likewise, community leaders far removed from a smaller impoverished demographic may be unaware or unprepared to proactively alleviate threats.

Peters suggests economic inequalities can be addressed through a “public investment in quality education and jobs, and a tax system to support such investments.”

Specifically, he suggests that economic development programs focus efforts to expand and attract full-time jobs that are at least moderately skilled, pay above average wages and offer benefits.

Too many rural counties are suffering from a current or former investment in one key employer. When that business relocates or, worse yet, shuts down, a domino effect impacts every facet of the community. Schools and governments are left with fewer resources. Individuals often take lower-wage opportunities or move to access similar wages. The number and quality of faith groups decline. The larger business community either learns to exist on less revenue, or shutters its doors.

Evidence of this decline is found in rural towns throughout the state.

What small economic development efforts need are a comprehensive approach — one that can only exist through coordinated efforts by our state leaders.

The inequities of Tax Increment Financing — that the state backfills a portion of school funds, but ignores absent county revenues — should be addressed this Legislative session.

The condition and safety of highways in rural areas needs to become a state priority, since transportation is a key factor in where businesses choose to locate. While we’re at it, we can develop a 10-year plan for bridge improvements.

The state needs to revamp development moneys in acknowledgment that rural areas can’t exist on motel-hotel taxes, and there need to be additional and specific incentives for businesses that choose to launch, build or expand in rural communities.

Finally, we need to have a “Come to Jesus” meeting on the reality of an unsustainable economy built on the back of inflated commodities, casino revenue distribution, low-wage service jobs and multiyear, increasing tax breaks for businesses. It is of little use to train a worker for a job that doesn’t pay a living wage.

When we place our eggs in multiple baskets and start building things in Iowa again, we will begin to see our towns and rural spaces revitalized.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on Sept. 21, 2014.