When a young person commits any level of crime, interventions should result in altering the youth’s behavior in a way that reduces delinquency and improves the youth’s chances of prosperity in adulthood.

These twin goals serve society’s broad interests and, when they intersect with reduced taxpayer expense, provide a solid foundation for the reduction of racial disparities within our juvenile and adult justice systems.

After all, the ways in which we interact with youth today set a framework for the future relationship between that individual and the larger community.

There are many reasons to applaud the first-in-the-state diversion program in Johnson Countythat seeks to protect young first offenders from entering a juvenile justice system that too often introduces them to and keeps them in contact with higher-risk youth. Researchers have sounded alarms for years that although this association — dubbed “peer contagion” — does temporarily prevent misbehavior, it can and does often lead to subsequent offenses.

Currently, 66 percent of juveniles referred to the Juvenile Court System do not reoffend. About a quarter of the referrals will be placed in the system two or three times, and only 8 percent will have four or more referrals.

In other words, for the majority of youth who are arrested, their first offense is not a harbinger of future criminal behavior. And, if there was a way to accomplish society’s twin goals without exposing youth to peer contagion influences, these statistics could skew even further toward single instances of bad judgment and behavior.

Perhaps more immediately important to citizens, removing these low-risk youth from the juvenile justice system frees existing resources and allows greater focus on those with higher and more violent risk levels.

While this may appear as some new, bleeding heart response to an overwhelmed corrections system and welfare state, the truth is the Johnson County program is rooted in the findings of a 1967 federal report by a presidential commission on law enforcement, which also advocated diversion for most youth that come into contact with law enforcement.

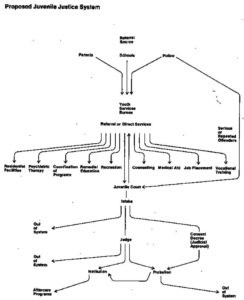

A graph of the group’s proposed juvenile justice system shows several avenues of processing including access to behavioral health and vocational services, with only “serious or repeated offenders” being taken by law enforcement directly to Juvenile Court.

But a key part of the 1967 report (as well as more recent studies on diversion) is that simply providing an alternative path isn’t enough.

Neither of the twin goals above are achieved if youth don’t receive individually tailored responses to their actions and situations. Those who are diverted with merely a reprimand and dismissal are as nearly likely to reoffend as youth offenders who were not diverted.

“They may already have delinquency records. They may be delinquent but not seriously so. They may be law-abiding but alienated and uncooperative in making use of education or employment or other opportunities. They may be behavior or academic problems in school, or misfits among their peers, or disruptive in recreation groups,” noted the 1967 authors.

“For such youths, it is imperative to furnish help that is particularized enough to deal with their individual needs but does not separate them from their peers and label them for life.”

It is in this area, I think, that the Johnson County diversion program misses the mark.

Roughly 1 out of every 7 juveniles accused of disorderly conduct in Johnson County during 2012 were white. Comparatively, eight out of every 9 juveniles in Johnson County are white.

That’s the very definition of racial disparity and disproportionate minority contact with the juvenile justice system.

Given the success statistics of similar programming in other states, there’s little doubt that this initiative will result in keeping a larger swath of youth out of Juvenile Court.

But it will not address other underlying issues that contribute to why certain juveniles are more likely to be removed from a school classroom, involved in a fight or stopped by a law enforcement officer.

It tosses a very narrow net on the overall problem of disparity.

But, maybe, for now, that’s OK because it signals and will prove collaborative success among the handful of organizations involved. With any degree of luck, more offenses will be added to the diversion list and more organizations will join the fray.

While there is no need to subject our youth to a host of services, which can ultimately be detrimental, we should be prepared with a wide variety of service options so that communities can respond quickly and efficiently to an individuals needs.

Perhaps, once immediate reactive needs have been met, the community can work toward a more proactive means of supporting our youth that can turn disproportionate contact into no contact at all.

Author’s Note: This report was updated June 30 to reflect 1 in 7 juveniles in Johnson County accused of disorderly conduct were white. In the previous version, this was accidentally flip-flopped.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on June 30, 2014.