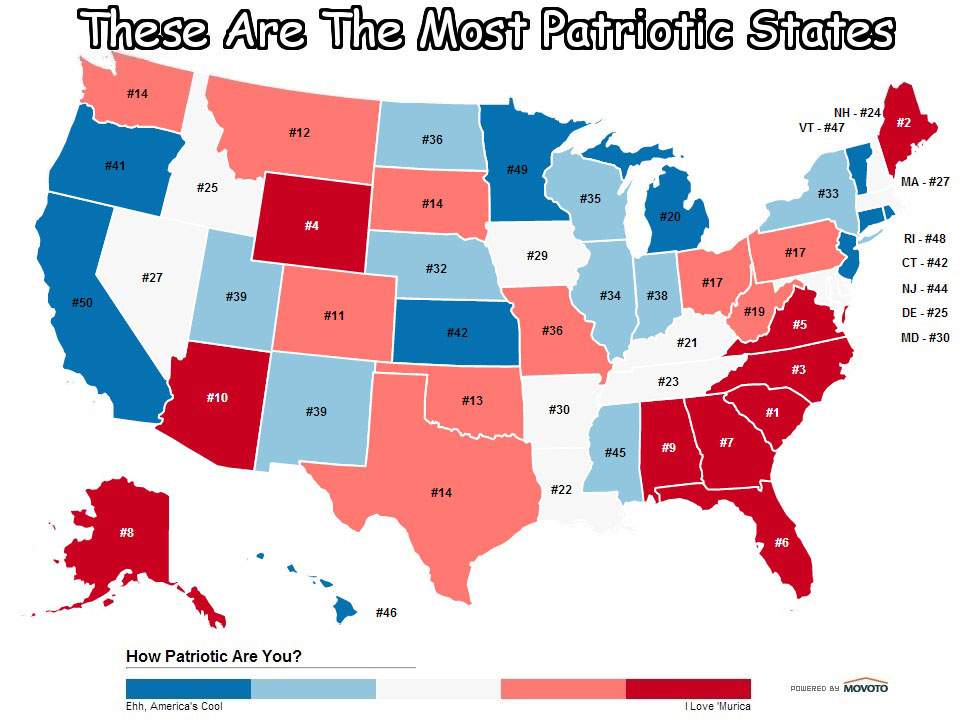

I was fascinated this week by a new patriotism survey of the states by a blog generally devoted to ranking U.S. cities and developing novel ways of looking at the real estate market. Then I read the criteria for the rankings.

Patriotism was measured, said the MOVOTO bloggers, on the following criteria:

• National Historic Landmarks per Capita

• Veterans per Capita

• Money Spent to Fund Veterans

• Percent of Residents That Voted in the Last Presidential Election

• People Who Google for American Flags to Buy

• People Who List America as an Interest on Facebook

As you might guess, based on those standards, Iowa ranked in the middle of pack, falling squarely in slot number 29 between Nevada (which tied for 27) and Arkansas. The only criteria where Iowa placed in the top 10 was voter turnout.

I don’t fault or admonish the bloggers for this. Quite the contrary, I applaud them for the novel use of the measures at their disposal.

But it does beg the question of how patriotism is and should be defined.

Too often, I think, we base assumptions of patriotism on the presence of the American flag. Politicians wear it, often “made in China,” on their lapels. Leaders at all level of government appear on stage with the American flag, their respective state flag and whatever flag best represents the point of their presser. Sports enthusiasts drape the flag over their shoulders or shake it above their heads at international competitions. We purchase flag emblazoned products by the shipping crate — everything from paper plates to clothing, from jewelry to stickers. In social media circles, we show off our Photoshop skills by placing text or silhouettes upon a background of the red, white and blue.

As fun and festive as this all might be, it’s worth pointing out that the vast majority of what we do with our flag is a violation of the Flag Code. And, truthfully, when taken alone, such displays are a poor measure of patriotism.

Whenever I think of patriotism, the image of my father comes to mind. As far as I can remember, he never wore a shirt or hat with the American flag. Instead, he wore a scar that ran the length of his lower leg, a physical and lasting memory of his time in the military.

I also remember the tear-rimmed brown eyes of the World War II veteran I interviewed years ago, and how his voice cracked and lowered to a whisper as he told me about a lamp he saw at a Nazi concentration camp. It was with equal portions of disgust and apology when he said, “the shade was crafted of human skin.” Then he turned away, aghast to have spread his horrors to another generation, and added, “I didn’t intend to tell you that.”

The place where I’ve felt most patriotic wasn’t at a political event or a speech or a parade. It was standing in a small park in Coweta, Oklahoma. The park is a mixture of past and future, with playground equipment in one spot and memorials to fallen soldiers in others. This spot is especially close to my heart because it was dedicated as the Jimmy Lee Campbell Memorial Park and Jimmy was my brother and one who fell while serving in Vietnam.

The small town of Coweta, which is located just east of Tulsa, lost more men per capita in the Vietnam War than any other place in the U.S. So while the park bears my brother’s name, it also honors three cousins and five other family friends. Mark Hatfield, a friend who served with my brother in Vietnam, escorted Jimmy’s body back home in 1970 and always had time for our family in the years that followed, is responsible for the green space. It is located on the property where he grew up, and just across the street from where my grandmother lived.

While I could write volumes regarding my thoughts on Vietnam and the brother that left this world far too soon, those are hardly the reasons I feel most patriotic when I stand in his park. When I am there, listening to the children play or watching a hand brush across a name on one of the memorials, I feel connected and invested in a way that I’ve never felt anywhere else.

It isn’t just that I want to make good on the sacrifices of the past, I want to make good on the promises of the future. And in that space I know, I can feel that there are millions of others who are of the same mind.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on July 6, 2014. Graphic credit: Movoto