This past week has been filled with listening and searching, both producing little satisfaction.

On Tuesday night about 80 people gathered at the Iowa City City Hall to discuss the future of two small buildings on South Dubuque Street. The buildings, known locally as the worker cottages, have sparked disagreement.

The property owner, Ted Pacha, wants to demolish the structures, literally paving the way for new development in the railroad district. Preservationists hope to save them, saying they represent a segment of the population and a moment in time unique to Eastern Iowa and of which too little already remains.

While much discussion at the public hearing centered on whether or not the structures were of historical significance — perhaps due to the narrow question before council members — the fact is the significance of the cottages is not at issue.

At the local level, all three Iowa City cottages had been recommended for status as historic landmarks by the Historic Preservation Commission and Planning and Zoning Commission. Following a December meeting of the state Historic Preservation Commission, the cottages were determined to be historically significant and, if still standing, are expected to be officially designated as historic landmarks later this year.

City Council members, however, seem poised to disregard all such recommendations and allow all three cottages to fall. Following impassioned pleas by those on both sides of the debate, council members punted. Instead of providing those in attendance an up-or-down vote, they chose to continue the public hearing to the Feb. 9 meeting, and further discuss the issue with planning and zoning members in the interim.

But, even with official historic landmark status, which was pursued without the cooperation of the property owner, it is likely the buildings will not survive. Such a designation indicates what is worthy of protection and preservation, but has few teeth to ensure it.

Owners of private property listed in the National Register have no obligation to open their properties to the public, to restore them, or even to maintain them, if they choose not to do so. Owners can do anything they wish with their property provided that no federal license, permit or funding is involved.

If, however, a property with a historic designation is slated for demolition, the property owner will likely need to minimize the loss to the larger community.

Perhaps the most recent example of this type of mitigation occurred following the 2008 floods when Hancher Auditorium was demolished. University of Iowa photographers and videographers captured as much as possible to at least partially preserve the 40-year history of Hancher, its architect and the many performers it hosted.

An exact course forward in terms of possible mitigation on the cottages has not been publicly discussed.

(Author’s note: The paragraphs between this point and the subheading below were added on Jan. 26, 2015, following reader feedback.)

If the remaining two cottages are given a local landmark designation, however, their future is more optimistic. Each city can develop its own local landmark rules, and those in Iowa City are more strict than national considerations.

When an Iowa City property is made a local historic landmark, any changes, including demolition, have to be reviewed by the local Historic Preservation Commission, which follows the City of Iowa City’s Historic Preservation Plan.

While this review does not permanently protect the cottages from demolition, it does add another layer of protection. Further, a look at the Historic Preservation Committee’s previous reviews shows that the bar for granting demolition has been set fairly high.

IOWA CITY COTTAGE – LISTENING & SEARCHING

Petitions, vigils, demonstrations and the historic landmark application for the Iowa City cottage properties have made it relatively easy for someone (like me) with very little information on their history to dig a little deeper.

The cottages date back to the late 1850s or early 1860s, only a few years after Iowa became a state and Iowa City served as the capitol.

Unlike other properties often earmarked for preservation efforts, these small structures are significant because of their insignificance.

That is, they are not indicative of how the most affluent in Iowa City lived at that time, but of how lower income and likely entrepreneurial citizens lived. In both the near and distant past, the structures housed a commercial enterprise at street level and provided residential space above.

The cottage at 608 S. Dubuque St. sold in 1859 for $200, the price likely reflective of previous soaring value (when the rail line was completed in 1856) combined with a world economic crisis in 1857. While some argue the cottages are connected to certain significant families in Iowa City’s distant past, state review has not confirmed this as accurate.

While these structures are some of, if not the most well-preserved examples of typical worker housing at the time, and largely unique to this region of Iowa because of the railroad’s influence, that’s not the portion of their history that I find the most fascinating, even if it is the ultimate reason for their statewide and national historical significance.

Philip Beck was one of several local residents to speak on behalf of preservation of the cottages. Specific to his plea was the Iowa City cottage at 610 S. Dubuque St., which is the current home of Suzy’s Antiques & Gifts.

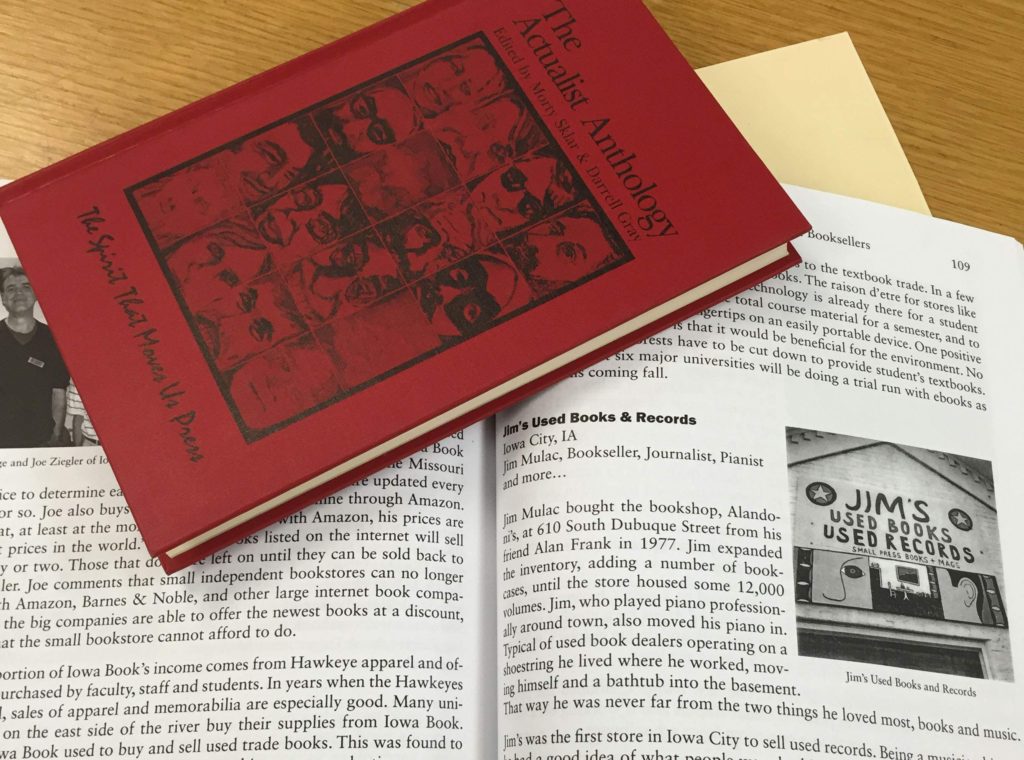

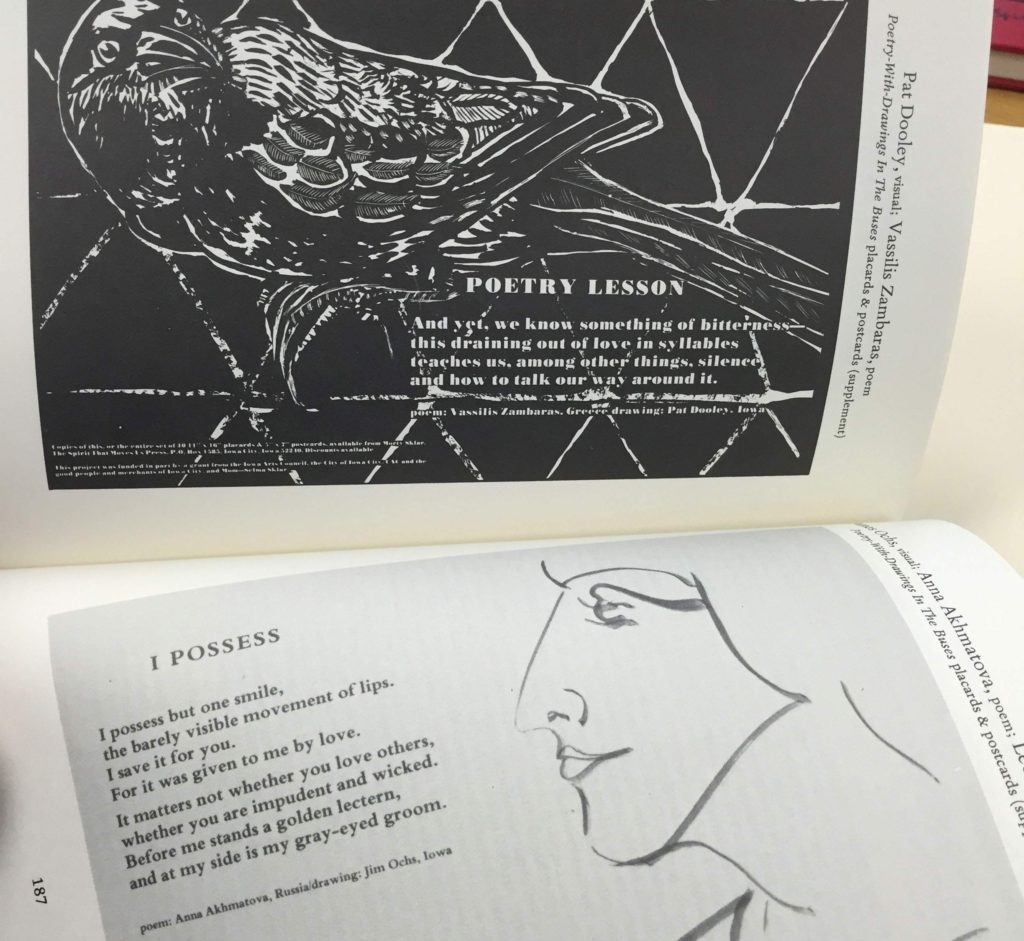

Beck, who has been a part of the Iowa City community for more than 40 years, made his points while gesturing with a book of poetry. The middle cottage, as it turns out, was once home to Jim’s Used Books and Records, which served as a meeting and performance location for the 1970s Actualist Poetry Movement.

According to author Joseph A. Michaud, as part of his look at the book trade in Iowa City, “Booking in Iowa,” in 1972 the Actualist Poetry Movement began in Iowa City and was comprised mostly of members of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop who wanted to further explore ways communication that were not confined by academics.

Jim Mulac, of Jim’s Used Books and piano-playing fame, was part of this movement, as were Anselm Hollo, Morty Sklar, Allan Kornblum and several others. Sklar was a close friend of Jim’s, founded “The Spirit That Moves Us” press primarily to publicize the movement. (He continues to operate the press today from New York.)

The publicity and talent, combined with relocation by some members of the movement, was largely successful. The Actualist Poetry Movement that was founded in Iowa City soon spread to California and other locations. Based on what I’ve read and heard, it is the only such movement to originate in Iowa City — at a time when the “City of Literature” was known as “Poetry City.”

While Jim’s Used Books was not the only place in Iowa City that was used as a significant gathering and performance spot by groups of members of the Actualist Poetry Movement, I’ve convinced the middle cottage on Dubuque Street is the last standing.

While a more detailed history is available in a Little Village Magazine piece written by Adam Burke, locations such as Epstein’s Books lost their gentrification battles long ago.

As I cold-called and approached people who are involved in the preservation of Iowa City and Johnson County’s history, few were well-versed in the Actualist movement and only a handful could provide places where the members planned — other than to point to a now much changed railroad district. The region is incredibly fortunate that so many members are still living and contributing.

In some ways I can understand the stance of those who are unwilling or unmotivated to preserve the Iowa City cottage properties as vestiges of ordinary people during the mid- and late 1800s. Although historians have said the cottages are exceptionally rare — especially when the three stood as a unit — it isn’t unimaginable to think there are other structures that also represent that moment in time.

What I’ve yet to understand is how a more recent history, one so incredibly specific to the underlying themes promoted by all facets of Iowa City — academics, writing, collaboration, innovation — can be so easily ignored and cast aside.

Unless residents are willing to accept a local tavern as the solitary representation and spot of remembrance for this movement, they must work to preserve the Iowa City cottage buildings.

Unless the themes of promotion for Iowa City are nothing more than propaganda, city leaders must preserve what they can of the Actualist Poetry Movement.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on Jan. 25, 2015. Photo credit: Lynda Waddington