Back roads have always been my friends, offering equal helpings of calm and clarity via a car window.

I turn on two-lane highways and gravel roads in the same way an alcoholic turns to a bottle, unable or unwilling to resist the siren call of a few moments of peace and possibility. The answers I seek may lie just around the next corner or just over the rise and, even if they don’t, I’ll still have a few moments before more unanswered questions arrive.

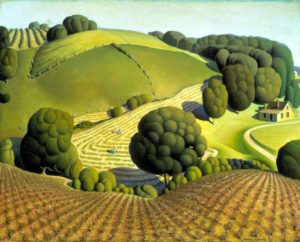

During one such binge a few weeks ago, as I passed through Maquoketa, my breath caught on rolling hills of farmland bathed in amber evening light. Unable to continue, I pulled to the shoulder to contemplate the Grant Wood reproduction etched by the setting sun.

Honestly, I’ve never been enthralled by Wood’s paintings, even as I recognize his talent. As I’ve listened to others describe their enchantment, my emotional detachment has become increasingly unsatisfying. Shouldn’t there be a mystical connection between two people that share the same birthday?

But in the dimming light that night something shifted. I saw a portion of the beauty, love and pride Wood locked into his memory and dedicated himself to preserving.

For days the experience festered, but remained sketchy — like being reintroduced to someone important, but unable to produce a name. A second event this week brought additional understanding.

During a discussion with Gazette colleagues about our ongoing series on rural Iowa, I was asked why I left my small hometown. While there are many little reasons, I replied with the larger, boiled down truth: “If I stayed, it would have been a failure.”

Young people in small communities are taught about those who once walked the same streets and went on to do great things. These are the “local folks made good.” Signs on the outskirts announce they once lived there; sometimes monuments are erected or street names are changed in their honor.

And while hero worship takes place everywhere, application is amplified and methodical in rural areas. The best and brightest are its most valuable exports, launched with uncanny precision toward lives in other places.

Staying would have been an affront to the people— teachers, coaches, counselors, religious leaders and, yes, parents — who had systematically planned my escape.

Like so many others, I have no hesitation saying where I’m from — I’m proud to be a small-town kid driven away on a cushion of dreams and well-wishes. Even without my sign on the outskirts, I’ve become a member of a fabled class of people: those who were from here.

Grant Wood, on the other hand, wasn’t simply from rural Iowa. Wood was of rural Iowa.

Yes, he physically left many times — even traveling to Europe to hone his craft — but he didn’t mentally stray. To say Grant Wood returned is a failure to understand he never left Iowa behind.

When his skill and talent were harnessed, he bettered what he was beholden to value — facilitating the return of artists John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton to the Midwest and launching a style of art unique to the region.

If the wish is to preserve rural places and way of life, youth must be offered a different narrative of success.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on June 7, 2015.