No doubt you’ve heard about the Women’s March and the March for Science. Let me tell you why more than 1,000 doctors marched on Washington earlier this month.

Physicians and medical students converged on Capitol Hill to advocate for continued funding of teaching health centers, which offer medical residency programs in community settings. It’s one of the programs under the umbrella of the $7.2 billion Community Health Centers Fund, slated to end Sept. 30 unless Congress takes action.

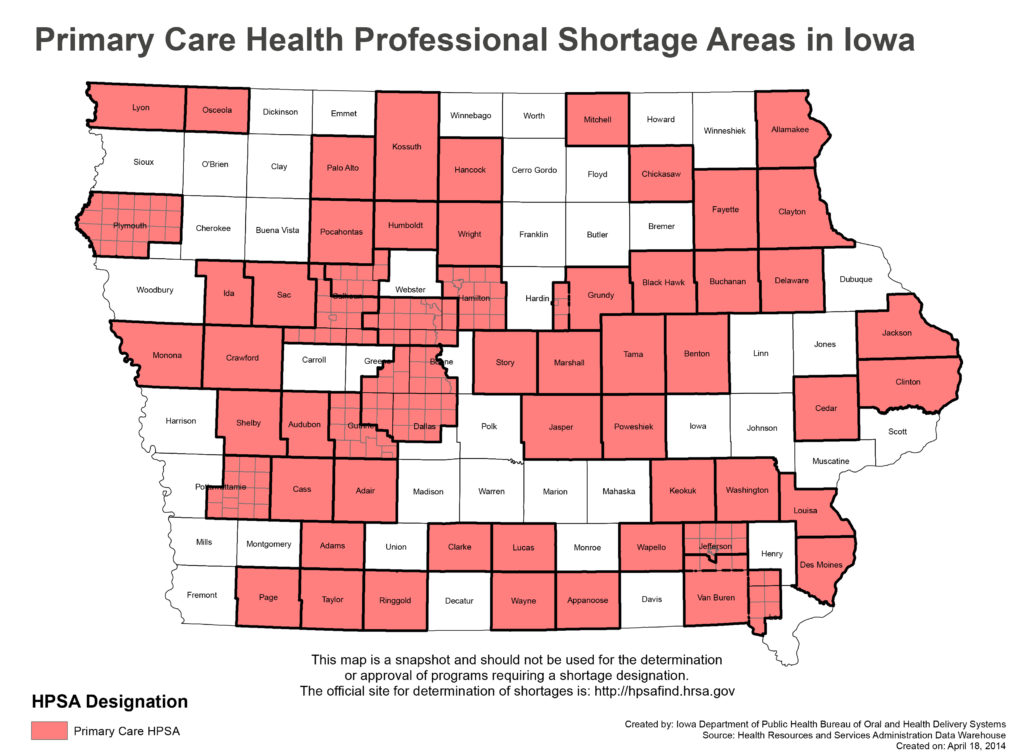

The combined programs support local access to medical care for thousands of Iowans and millions of Americans. They’re especially vital for rural health.

Teaching health centers — one of which is located in Des Moines — provide medical residency programs in community settings. Residents are trained in family and internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry and dentistry. The program is especially vital for underserved rural areas because most family physicians set up practices within 50 miles of where they train.

Past graduates of the Des Moines-based program have taken positions in rural communities, as primary care doctors or as part of emergency rooms. Others have accepted fellowships in community health or geriatrics. Since 2013, Primary Health Care has received nearly $11 million in federal grants to operate the teaching health center in Des Moines.

It’s a high-demand program with far more applicants than openings and, more important, it’s working. Teaching health centers produced more than 700 new doctors in 2015 and 2016 and, according to the American Osteopathic Association, could nearly close the physician shortage by 2020 if lawmakers continue funding. The Des Moines-based program currently has 12 residents.

The other alternative, according to a 2016 American Medical Colleges report, is a shortfall of between 14,900 and 35,600 physicians by 2025.

It’s also a sound government investment that spurs local economies. The AOA estimates that while teaching health centers make up less than one percent of the federal outlay for training physicians — funding was cut nearly in half during a two-year reauthorization of the program in 2015, providing $60 million in FY2016 and FY2017) — each resident in the program generates $200,000 in annual economic benefit to the community and $1.9 million every year they practice in the area afterward. Every physician who practices in a medically underserved community nets $3.6 million in annual savings for the health care system — through early diagnosis and fewer serious illnesses.

Also part of the fund are the nation’s roughly 9,300 community health centers, which provide care for patients in similarly underserved communities regardless of their ability to pay. More than three-quarters of the patients who visit such facilities are either uninsured or covered by Medicaid. Fully 72 percent earn below 100 percent of the federal poverty level. Funding for the health centers was increased as part of the Affordable Care Act, because the law combined with Medicaid expansions increase health center patient rolls. The number of patients seen at community health centers has increased by 42 percent since 2008, hitting the 25 million mark this year.

Iowa is home to 14 federally-qualified organizations — 13 community health centers and one migrant health center. They provide primary and preventive health care services at 38 full-service sites and 33 satellite locations such as schools, nursing homes and homeless shelters. About 45 percent of Iowa health center patients receive Medicaid, and 93 percent are at least 200 percent below the federal poverty level.

A third program within the fund, the National Health Service Corps, offers scholarships and loan forgiveness to doctors who agree to practice in high-need areas.

Tucked within these three high-level programs are, of course, many other smaller initiatives that use grant money from the Community Health Center Fund. Since 2011, more than $100 million has flowed into Iowa for services like opioid and heroin treatment, health center training and technical assistance, behavioral health integration, patient-centered medical homes and facility improvements.

When put together these programs provide assurance to rural residents that they can see a well-trained primary care physician within a reasonable distance of their home.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on April 30, 2017. Photo credit: Iowa Department of Public Health