No one knows exactly how many veterans are buried in cemeteries in the Corridor without headstones or other markers of their sacrifice. On this day, however, we know there is one less.

Leonard L. Kelly, area veterans believe, may be the only Cedar Rapidian to receive mortal wounds on the beaches of Normandy during the June 6, 1944, D-Day invasion of World War II. He suffered for two weeks before dying, according to War Department communication with his family.

It took another five years before his body was returned to Iowa and subsequently buried in Cedar Memorial Cemetery.

What happened afterward is mostly a mystery.

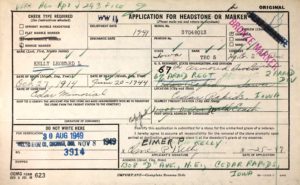

His brother, Elmer P. Kelly, applied for a military grave marker, but there’s no record it arrived. And even if it did, it certainly never was placed. Over time Elmer and other immediate family members died, taking vital information with them.

The family home, on D Avenue NE near Coe College, has been demolished, the land now a parking lot.

For nearly 70 years, when the nation paused to honor veterans who gave the ultimate sacrifice, Kelly was overlooked. But not this year.

A full military service will be held May 4 at Kelly’s gravesite. A new headstone has been placed, courtesy of several veterans organizations working with Cedar Memorial.

Kelly finally will receive the community recognition that has eluded him for too long.

More than 60 years passed between Kelly’s burial in Cedar Rapids and Story City resident Becky Watson’s receipt of an unusual email from her friend Adrian Caldwell of Tupelo, Miss.

Caldwell had been contacted by Michael Blackburn of Oklahoma City, Okla., who had purchased a Purple Heart bearing Kelly’s name in an online auction. Blackburn contacted Caldwell after researching Kelly and learning that he had been part of the same regiment as Caldwell’s father. Watson’s father also had been in that regiment, and Caldwell reached out to her Iowa friend.

“Michael Blackburn purchased the Purple Heart without any questions as to why the person was selling it,” Watson said. “He just did not want it to fall into the hands of someone that would disrespect it.”

Watson made arrangements with the Iowa Gold Star Military Museum in Johnston to keep and display the medal, and it returned to Iowa in spring 2011.

Four years later, when Watson traveled to Cedar Rapids to attend a state bowling tournament, she made calls to the Department of Veterans Affairs and local officials to locate his gravesite, and she and a friend visited.

“We didn’t find anything,” Watson said. “I was sure we were either in the wrong location or maybe had been given wrong directions. … There was just grass. Not a stone, not a temporary marker … nothing.”

Watson reached out to Don Tyne, director of Linn County Veteran Affairs, which began a massive search of historical and military records.

“Once we are able to show death records, application for the marker and that none had been placed, we were able to receive a new bronze marker,” Tyne said. “It’s hard to stomach that each year when veterans groups and their volunteers, like the Boy Scouts, went out to cemeteries to place flags, Kelly wasn’t included.”

Once the bronze marker arrived, it needed to be mounted on a stone and placed on Kelly’s grave. Cedar Memorial offered the granite at a discounted rate, and nearly every veterans’ organization in Linn County chipped in to help cover the cost.

“The veterans in this community — especially the older vets — have a strong sense of honor,” said Ron Williams, Linn County Veterans Charity Fund chairman. “We take care of our own.”

With the marker now in place, the groups are preparing for the May 4 event.

EARLY LIFE

A few newspaper clippings and historical documents are all that remain of Kelly’s life.

He was born in Cedar Rapids to Emma (Tellin) and George Shadle in October 1913. He had two older brothers, Clyde and Chance, according to records in the Linn County Genealogical Society.

When his father died in 1918, the family moved to the D Avenue home of their grandfather, Joseph Tellin.

About two years later Emma remarried and, within a few years, all of the boys had begun using the surname of their stepfather, Charles Kelly. Two more children were added to the family — Elmer Patrick in 1922 and Goldie May in 1924. There was also a half-brother, William Leroy.

No records show where Leonard went to school, or if he graduated, although their address indicates he likely would have attended the former Franklin High School as part of the class of 1931 or 1932.

Following school, he worked at Quaker Oats and remained active in the community.

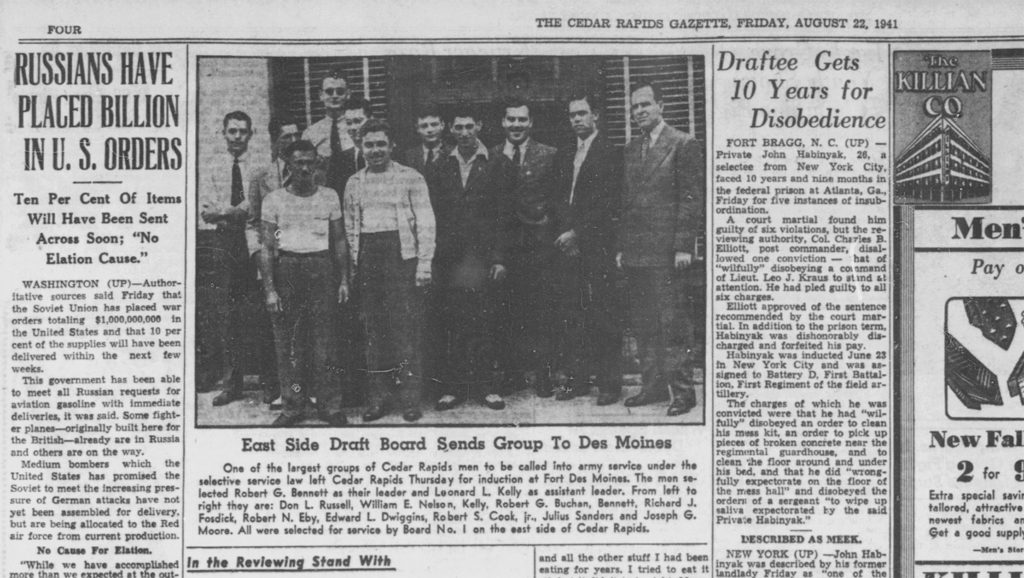

In 1941, Kelly was one of 10 men named by the east-side draft board for induction into the Army. Elected as assistant leader of the draftees, Kelly and the group left 10 days later for processing at Fort Des Moines.

On Christmas Eve 1942, while on a 10-day furlough home, Kelly married Mary Josephine Pachta, whom he had known for three years. They had a small reception in the home on D Avenue where “a miniature soldier and bride topped the wedding cake” on the weekend before he shipped out to Africa as part of the 67th Regiment, 2nd Armored Division, nicknamed “Hell on Wheels,” according to a 1942 Gazette story. Kelly earned the rank of sergeant (TEC 5) while serving as a mechanic.

His family and new bride never saw him again.

A hearse from Cedar Memorial picked up his body at Union Station in Cedar Rapids in late August 1949. Kelly’s mother and brother paid $48 in cash for the funeral and burial, held on Aug. 26. Kelly was 30 years old at the time of his death.

BEYOND LEONARD KELLY

While the story of this one veteran, his lost artifacts and community members intent on doing the right thing could end with the upcoming community service, Kelly’s legacy will endure for many more years.

“This situation made us aware of a problem,” said Julie Freese, a family service counselor with Cedar Memorial. “We learned that we have veterans buried without memorials and, now that we are aware, we don’t find that acceptable.”

According to Freese, the business is working with the Marine Corps League to locate any such graves in Linn County. If the burial sites have been dormant for a certain period of time — no one has placed flowers or kept up the site — Cedar Memorial will significantly discount its cost so that area veterans groups can appropriately mark the graves.

The government provides a plaque-like military marker for veterans at no cost — provided the proper paperwork is submitted — but it must be mounted on some type of stone, usually granite.

An initial search of only Cedar Memorial Cemetery by its staff has located two more veterans that may require the community’s help.

“We don’t plan to stop there,” Freese said. “… Our intention is to work with cemeteries throughout the county and make sure that all of our veterans are remembered and honored.”

The initiative echoes the spirit of a new state law that allows nonfamily members to retrieve and bury the cremated remains of veterans stored in Iowa funeral homes. Whether due to homelessness or other factors, these veterans, once claimed, will be buried at the Iowa Veterans Cemetery in Adel with full military honors. (No fee is charged for veterans to be buried at the state-run cemetery.)

The new law goes in effect July 1. If the remains are that of a veteran, they will remain with the local director for an additional period of six months, to provide time for a family member to come forward. Funeral directors can release unclaimed remains to a local veteran groups.

“As the situation with Kelly has made clear, it doesn’t matter when the veteran lost his or her life,” Williams said. “What matters is that we take the time to show proper respect and recognition of the service.”

IF YOU GO:

• What: Several area veterans groups will pay tribute to Army Sgt. Leonard L. Kelly, who lost his life from wounds received in the Normandy invasion during World War II and only recently received a proper headstone. Following the military rites, Cedar Memorial is offering light refeshments in its on-site chapel.

Kelly’s Purple Heart, returned to Iowa after being sold in an online auction, will temporarily be on display at Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Cedar Rapids. It is a permanent part of the Iowa Gold Star Museum’s collection in Johnston.

• When: 1 p.m., May 4

• Where: Cedar Memorial Cemetery, Woodlawn section near the pond and main entrance

This feature news story by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on April 24, 2016. Photo credit: Adam Wesley/The Gazette