When you think about violence against law enforcement, you probably don’t turn a suspicious eye to your smartphone. But some police advocates are doing just that.

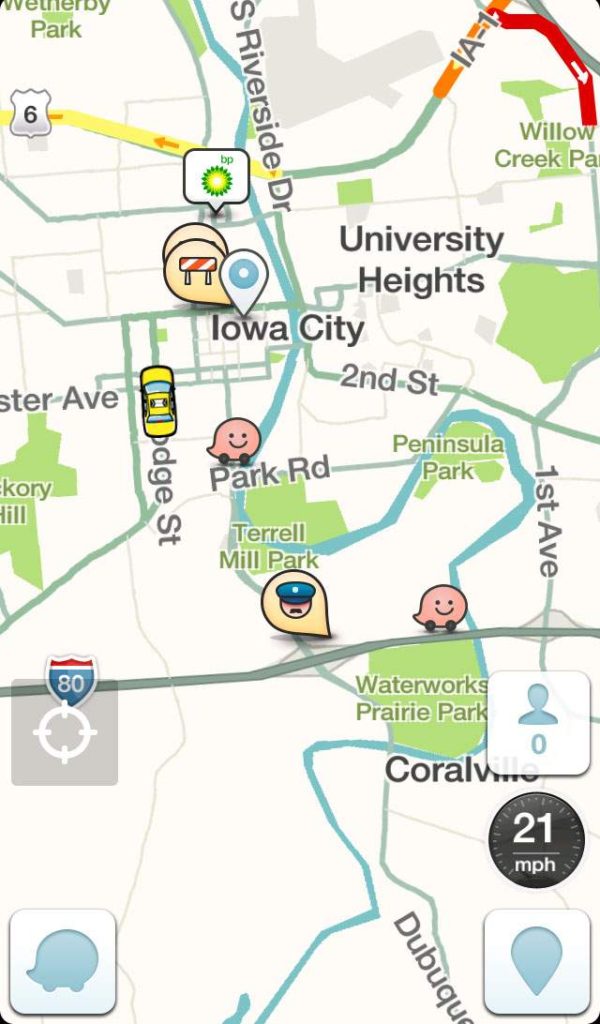

Waze, a navigation app, has drawn the ire of some police officers who believe its “cop-tracking” capabilities pose a threat.

I’ve been a happy Waze user for several years, long before it was purchased by Google in 2013 for $966 million.

The app works like most other navigation programs, showing drivers the way from Point A to Point B, but it also crowdsources real-time driving data based on traffic flow and road hazards.

If you hate driving through a larger city at rush hour, need to arrive at your destination by the quickest route possible or want to avoid traffic cameras, Waze will be your best friend.

Waze gathers and analyzes the experiences of all other drivers in the area using the app, presenting it to you and, in some cases, automatically adjusting your route to avoid trouble spots.

Some of what it gathers — traffic speed, for instance — is automated, requiring no manual interaction between the app and the user. Other items, such as road construction or hazards, are manually reported by the driver or passenger pressing a button. As more app users travel through those areas, they are notified of what’s been reported and asked to confirm if the issue remains a traffic problem.

This is the app feature that has drawn the scrutiny of law enforcement because, in addition to road construction, Waze users can also report (and notify other drivers) of a police presence. Officers taking issue with this feature have referred to it as “stalking” or “cop-tracking,” saying it could be used by criminals to locate and harm.

The uproar seems to stem from the Instagram (photo-sharing) account of Ismaaiyl Brinsley, the gunman involved in the shooting deaths of two New York Police Department officers in December. Brinsley posted a screenshot from Waze as well as threatening messages. Although no link between Waze and the deadly shootings has been found — Brinsley discarded his phone more than two miles from where the shootings took place — that the gunman had access to the app seems to be enough.

As is typical, the controversy is born of misunderstanding. Waze does not “track” or “stalk” police. Even when drivers choose to report, the notifications represent only a single point in time. Once an officer moves to a different location, the notification is no longer accurate.

My experience has been that notifications of police on the side of the road are accurate about a quarter to a third of the time. Since the data is real-time, accuracy is very dependent on the density of Waze users. Nonetheless, I’m betting other Waze users, like me, check their speed every time such a notification pops up.

And, also on the positive side, reporting an accident with Waze allows other drivers to be routed around the area, making clean up safer and more manageable.

There are many conversations that need to take place as we work to keep our law enforcement officers safer. This one, however, is a red herring.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on Jan. 31, 2015.