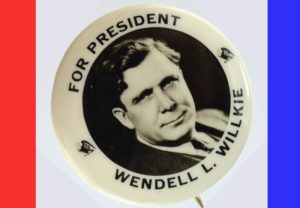

This is what happened in 1940 when Republicans opted for a political outsider

National pundits pondering what a Donald Trump nomination means for the Republican Party and the nation have been reading the tea leaves. They’d be better off reading history books.

This isn’t the first time party activists have engaged in friendly fire or looked beyond political loyalists for a savior. Seventy-five years ago Repubicans decided a businessman was their best presidential bet.

Like Trump, Wendell Willkie, the GOP’s 1940 presidential nominee, once considered himself more left than right. Less than a year before he was named the GOP nominee, Willkie was registered as a Democrat.

And he too bucked the establishment. Willkie didn’t run for the nomination, instead taking a stand at the party’s national convention in Philadelphia. While his vocal supporters, many of them younger voters, generated chatter, Willkie, already famous, sought out uncommitted and soft convention delegates.

The campaign took place in front of a backdrop of the German armies led by Hilter marching across Europe, decimating American allies. Before the convention, Republicans support was centered behind candidates who favored less U.S. involvement in the war, and specifically on Thomas Dewey, a young district attorney from Manhattan.

Politically charged and well-liked Willkie had never held elected office. The former Firestone Tire and Commonwealth & Southern executive lawyer positioned himself as a friend to American business interests. He was an outsider — independent and self-sufficient — someone who could take on established political players with American grit and an unpolished smile.

Willkie broke ranks with Democrats when he believed the party, largely due to the New Deal, had run amok and threatened the business foundation that made this country great. He’s the man who famously stated, “I did not leave my party. My party left me.”

Willkie broke ranks with Democrats when he believed the party, largely due to the New Deal, had run amok and threatened the business foundation that made this country great. He’s the man who famously stated, “I did not leave my party. My party left me.”

When Willkie said he would accept the GOP nomination if it came to him, James Watson, a Republican senator from Willkie’s home state of Indiana said he was fine with “the town whore” joining the church, but not leading the choir the first week.

And while such rebel-rousing will sound familiar to those tuned in to the 2016 presidential race, few would recognize Willkie’s positions as current Republican fare.

“Because I am a businessman — of which, incidentally, I am very proud — and was formerly connected with a large company, the doctrinaires of the opposition have attempted to picture me as an opponent of liberalism,” Willkie said. “But I was a liberal before many of them heard the word, and I fought for the reforms of the elder LaFollette, Theodore Roosevelt, and Woodrow Wilson before another Roosevelt adopted and distorted the word liberal.”

Willkie advocated for business regulation, collective bargaining, a minimum wage and maximum work hours, unemployment benefits and federal pensions as well as other “old age benefits.”

He was a fierce social justice advocate, which was widely appealing to New England’s more liberal Republicans. Years before his presidential bid, he led a successful push to oust members of the Ku Klux Klan from the Akron, Ohio school board.

But he was also a shrewd businessman and attorney, battling the Roosevelt administration all the way to the Supreme Court on behalf of the utility companies opposing the federal process for rural electrification. Although ultimately losing, Willkie gained national acclaim for his work on behalf of shareholders and was widely perceived as a businessman with a heart. He appeared on the cover of Time Magazine in July 1939 and Fortune Magazine in April 1940.

Despite the shift in GOP priorities or Willkie’s well-liked public persona, it’s still difficult to imagine a recent Democratic Party activist thwarting the GOP establishment to rise to the top of the ticket. The answer lies in how badly the party was divided and the refusal of establishment candidates to set side ego.

Three candidates — Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan and District Attorney Dewey — were expected choices when the party gathered in Philadelphia. Other potential nominees simply showed up at the convention and made their case. According to author and historian Charles Peters, even former President Herbert Hoover attended the convention in hopes of garnering support, only to be disappointed by a faulty sound system that kept most delegates from hearing his call.

Willkie supporters held key convention roles — none more important than the arrangements committee, which determined the public observers allowed inside.

Establishment candidates soon realized their support was waning and flowing to Willkie. They began negotiating. In the end, however, none would accept less than the nomination.

Disapproval from the convention floor during Willkie’s nomination was quickly drowned out by a flood of supporters in the public balcony. They chanted, “We want Willkie!”

“Is the Republican Party a closed corporation? Do you have to be born into it?” asked Indiana Congressman Charles Halleck during the nominating speech.

Front-runner Dewey lost support between the first and second ballots, essentially creating a two-man race between Taft and Willkie. Still, neither Dewey nor Vanderberg withdrew. By the fifth ballot, Willkie was in the lead. After the sixth ballot, and after Willkie made a deal with the Michigan delegation, Vanderberg released his delegates. Most moved to Willkie. The seventh ballot made it official: Willkie was the GOP nominee.

The Republican Party shake-up came quickly afterward, with key party officials, including the Republican National Committee chairman, sent packing. And, at least initially, Willkie polled well against incumbent Roosevelt, who was nominated in the Democratic convention the following month. Third party candidates were wooed by those who felt disenfranchised, but none caught on.

There’s more to the story — there always is — but a quick summary is that Willkie began to drop in the polls. The campaign tried to redirect by adopting the talking points of disenfranchised GOP voters, but it was too late.

Behaviors that initially appealed to voters later pushed them away. Speaking to union workers, for instance, Willkie pledged a new secretary of labor “and it will not be a woman either.” The nation’s first female cabinet holder, Frances Perkins, was not amused and neither were women voters.

Roosevelt earned a third term by 10 percentage points in the popular vote, and a wide majority of the Electoral College. Willkie carried only 10 states, one of which was Iowa.

Perhaps because of Willkie’s previous Democratic Party ties, or maybe because he was a campaign novice, he attended a private meeting with Roosevelt the night before Roosevelt was sworn in for a third time. Roosevelt made Willkie the nation’s informal envoy to Britain, setting the foundation for an ongoing and public foreign policy debate between Willkie and Charles Lindbergh, another prominent Republican. The move effectively kept the GOP divided for years to come.

When most historians talk about Willkie, they do so in terms of how he impacted U.S. involvement in the war. No doubt Willkie, who largely agreed with FDR’s interventionist policies, negated most isolationist talking points during the campaign. Other historians laud his larger “One World” impact on American culture. Both accomplishments are important and should not be forgotten.

Looking back with only an eye on the Republican Party, however, Willkie was the harbinger of chaos. Many of the bitter geographical and ideological divides we see now have their roots in Philadelphia in 1940. Widespread relational changes between the federal government and the U.S. populace intrinsic to the New Deal and long opposed by Republicans were entrenched. Political coalitions that largely benefit politicians who run on the left — workers, African Americans and women — were forged and solidified under the dual umbrellas of economic decline and government intervention.

In 1940, Republicans had already twice lost the White House, once with an incumbent. The focus of their nomination contests didn’t center on who would necessarily be the best president or who best embodied their political values. They went looking for the person they thought could win the election, history and values be damned.

In Willkie they found a well-known, politically-charged man with the ability to draw large crowds and a penchant for speaking his mind. The deviations between his policy positions and those of the party were given a back seat, as were voters who disagreed.

Until his death in 1944, Willkie continued to work with FDR. It’s rumored that the two men were plotting a new political party, one that would realign populist voters split between Republican and Democrat into a unified home.

It’s a cautionary tale for Iowans on either side of the political aisle as they gather this week to winnow the presidential field.

This column by Lynda Waddington originally published in The Gazette on January 31, 2016.